Introduction

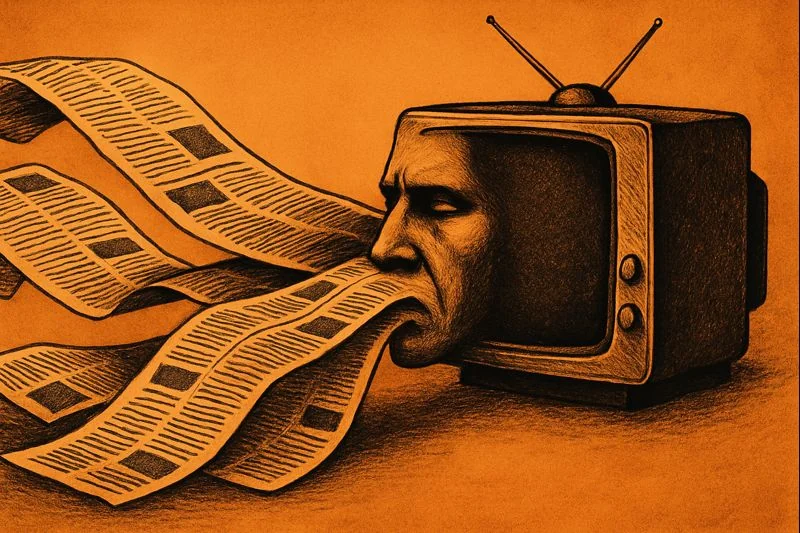

Today we live in a newsroom that never closes: notifications on the phone, a never-ending breaking news ticker, and updates that multiply from updates, until following the news becomes more of a habit than an effort to understand. In this climate, we seem to know more than ever, but understand less: we pick up many headlines, pass by short clips, and come away with a general impression that does not turn into interpretable knowledge or a stable critical stance.The central question here is: Why do we know more but understand less? The thesis is that the issue is not a lack of information, but a flow structure that decontextualizes the event and replaces the logic of following with the logic of passing. As Herbert Simon warned early on, information overload produces attention deficit and makes the real challenge managing the increase rather than accumulating more.

Contemporary research suggests that digital news environments measure value by reach and engagement. This is further complicated when algorithms intervene in the order of what we see, creating a personalized cognitive experience that can turn into a filter bubble that reduces friction with difference and weakens the ability to contextualize the event (Pariser, 2011).In the background, the logic of data mining and attention works as an economic resource, where memory itself becomes a raw material for platforms that profit from the continued flow (Zuboff, 2019), and this can also be read within what some researchers call data colonization that re-possesses daily life through constant measurement.

First axis: From news as an event to news as a flow

In traditional journalism, news was constructed as an event within a time series: gathering information, verification, narrative, and then follow-up that reveals developments and results. The meaning was not limited to the moment of publication, but to the surrounding backgrounds and files, and the reader has the right to return to the text itself as a reference.In the digital environment, the news has been redefined as a rapidly updatable unit, and the text has become a temporary version that can be replaced every minute. This shift comes not only from technology, but from the competition for attention: platforms reward speed, and publishers adapt to a rhythm that does not allow for slowness.As news consumption expands across social networks, search engines and apps, the news appears in fragmented interfaces: a headline, an image and a couple of lines, while the editorial context that once connected the story to what came before and after disappears. Reuters Institute reports document how access to news is becoming distributed across multiple platforms and how audiences are increasingly relying on algorithmic interfaces to discover stories, deepening the shift from news as a story to news as a pulse in a stream.

The logic of immediacy is the operating rule of streaming: everything is presented as now, even if it is part of a long process. Platforms enforce temporal rhythm through notifications and trends, and reorder importance according to a measurable standard: clicks, shares, and longevity. Here, the truncated headline becomes a tool of economy: it promises a quick reveal and postpones interpretation, pushing the recipient to scroll further.Instead of serving the audience, speed becomes a criterion for competition between publishers, reducing the distance between the event and its interpretation. This intersects with Simon's idea of the scarcity of attention in an information-rich world (Simon, 1971): when attention is a scarce commodity, systems seek to capture it through temporal urgency.

In the model of censorship capitalism, behavior, including the habit of pursuing the urgent, becomes an object of profit through prediction and direction, making continuity of flow an end in itself. As a result, the event is reduced to a tradable moment, while opportunities for quiet reading that reconstructs meaning are diminished.Algorithms not only accelerate publication, but also accelerate dissemination by enhancing what triggers an emotional response, expanding the space of immediacy at the expense of interpretation, and forming personalized circles of vision for each user, which increases the likelihood of reductionism and rigidity in reading. Live coverage makes the news a series of alerts rather than a returnable text (Pariser, 2011).

The effect of this disintegration is that meaning is no longer produced from a continuous narrative, but from plotless fragments of information: discrete numbers, truncated statements, and images that lead to quick conclusions. Cognitive accumulation requires patience and gradualism, while instant consumption acts as a short-term memory filled with adjacent units without causal links. With repeated jumping between stories, the mind gets used to receiving rather than interpreting, the question of cause and effect weakens, and the distinction between what is new and what is important fades away.

As everyday life is transformed into data that can be extracted and measured, a flash culture that favors signaling over understanding is reinforced. This can be seen in the rise of phenomena such as news avoidance or headline skimming, where some audiences feel overwhelmed by the flow without providing clarity, and the natural response is partial withdrawal or indifference, not because the event is trivial, but because its disjointed form prevents mental ownership (Newman et al., 2024).). When no narrative memory is formed, the past becomes just old addresses rather than a learned experience.

Theme 2: Awareness without context

When news is fragmented into quick units, the context that gives the event its meaning: historical causes, economic structures, and political trajectories that make the present an extension rather than a surprise. The flow does not explicitly dislike history, but it practically weakens it by turning the background into a temporal burden that does not fit into a facade designed for now.In the traditional format, the reader arrives at the news with a map: what came before, who were the actors, what are the possible paths? In the digital format, the reader enters the story, often in the middle, through a clip or headline that announces the result before the cause. As each user customizes what is shown according to their preferences, contextual gaps widen between different groups who see the same event from different windows (Pariser, 2011).

The news becomes an isolated piece of information, and history becomes a silent background that the system neither demands nor rewards. The more the constant measurement of everyday life becomes part of the structure, the more the context itself is compressed and reduced, because what is not easily measured is marginalized (Couldry & Mejias, 2019).Links may seem to provide limitless depth, but the actual experience is the opposite: the reader often stays in the interface layer, because moving between links means leaving the stream they fear losing. The Reuters Institute reports that a large part of consumption occurs through intermediary platforms, making access to stories from shortcut portals rather than from pages that preserve the narrative sequence (Newman et al., 2024).).

In a streaming environment, fragmented knowledge is formed: we know names, hashtags, and snapshots, but we do not have an explanatory model to connect them. The difference between knowledge and understanding arises here; knowledge may mean having information, but understanding means being able to connect it into plausible causes, relationships, and expectations.From an attention economy perspective, the issue is not that facts are scarce, but rather that attention is spread over a large number of competing signals (Simon, 1971). When relevance becomes related to what goes viral rather than what is explained, the more shareable stories take precedence over the stories that need to be explained.

Theme 3: From comprehension to passive reception

Streaming not only changes the quantity of what we see, but also reshapes our relationship to truth itself. When the criterion of visibility becomes the most circulated, the criterion of importance declines, and public debate becomes governed by who manages to grab attention rather than who offers the most accurate explanation. Algorithmic ranking creates layers of reality: each user sees a version close to their preferences, reducing the experience of common reference and increasing doubt that there is one truth on which to agree (Pariser, 2011).As news shocks are repeated without context, trust is gradually eroded: not just trust in sources, but trust in the possibility of understanding at all. Reuters reports that trust in news in many markets is volatile, and segments of the public express skepticism or fatigue, making the truth seem fluid and interchangeable with each new wave.In this sense, it is not just lying that becomes an issue, but also the fluidity of meaning: too many signals without an interpretive compass. In a model that profits from interactivity, provocation and division become the fuel that reproduces the flow (Zuboff, 2019).

The constant flow creates a comfortable environment for both authorities and platforms, not in the sense of conspiracy, but in the sense of structure: when the next news story overshadows the previous one, long-term accountability is weakened, and it is difficult to establish a narrative about responsibility and consequences. Platforms benefit from the circulation of attention because they measure and sell it, and authorities benefit from the short public memory because the blurring of the sequence gives them space to deny or redefine what happened.In what some scholars call data colonization, people become data sources, and controlling the rhythm of visibility becomes part of the soft control of the public sphere (Couldry & Mejias, 2019). With censorship capitalism, the pattern of directing behavior through prediction and immediate response is reinforced, making it harder to build a progressive debate or follow-up investigation (Zuboff, 2019).

In the end, news does not disappear, but it loses its temporal extension: it no longer accumulates knowledge, but consumes attention and then leaves a vacuum waiting for a new wave. Even when explanatory reports are published, they compete within the same interface, rearranged behind what is more sensational and trending. As audiences rely on platforms as their main access to news, the agenda of attention becomes short-sighted, which weakens follow-up and strengthens the logic of forgetting (Newman et al., 2024).

Conclusion: Reclaiming Memory and Understanding

This paper returns to its central question: "Why do we know more but understand less?" The answer that emerges across the three themes is that the issue is structural rather than individual. The abundance of news is not the issue itself, but the way it flows: news turns into a pulse, context fragments, and collective memory is formed as ephemeral tweets. In this climate, cognitive fatigue becomes an expected outcome, and the fluidity of meaning and loss of trust become side effects of a structure that rewards dissemination at the expense of interpretation.Reclaiming memory does not mean isolation, but building alternative conditions within the public sphere: contextual journalism that reconnects the event to its history, interpreting before rushing, and publishing models that allow for follow-up and retrievable archiving. At the level of reception, we need a conscious cognitive slowdown that redistributes attention as a scarce resource, and resists the logic of attention and data mining that makes flow an economic goal.

The question remains open: Can we develop practices and platforms that rehabilitate memory and understanding, without losing the ability to have instant access to what is happening in the world? Part of the resistance may be in editorial forms such as selected publications and slow coverage that reduce noise and increase depth, and part in public policies that impose transparency on algorithmic ranking so that society's agenda does not become a function of closed equations. Understanding streaming as a data economy helps to realize that memory is not only a personal matter, but also a battleground for who has the right to define the past and the present.

Comments