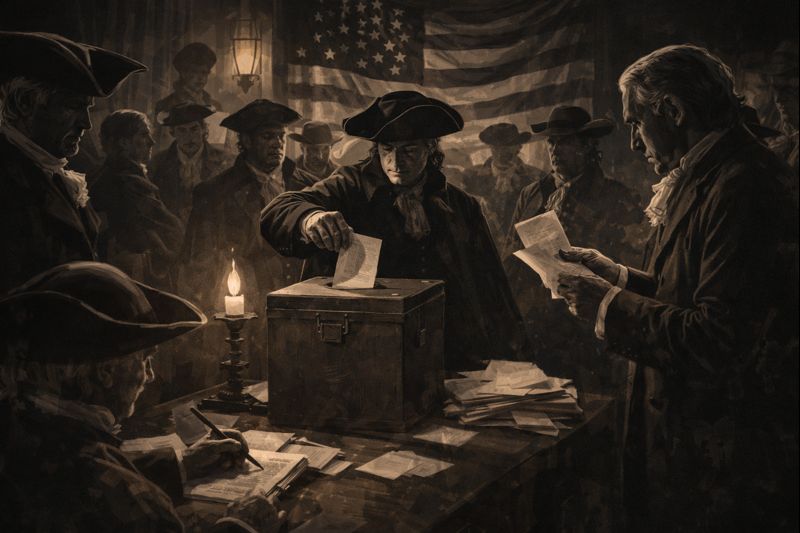

On this day, January 7, 1789, Americans were not preparing to go to the polls to choose their president as we know it today. What happened was simpler in form and more complex in effect: Congress set this day as the deadline for each state to select "presidential electors" who would then gather to vote in what became known as the Electoral College. This was the first practical step in the first presidential election in US history, an election based not on direct popular vote but on a selection formula unfamiliar even by the standards of the time.

The basic idea was that the people do not elect the president directly, but rather choose (or the state chooses on his behalf) a group of people, who give their votes to the president. Weeks later, on February 4, 1789, the voters voted, and George Washington won unanimously, then was sworn in as president on April 30 of the same year. There were no campaigns, no debates, and no actual competition, but the rule that was laid down then is what made everything that came after it.

The reason was not only technical, but also political and social. The new country was a federation of states that differed in size, population, and interests. There was a fear of two contradictory things: on the one hand, the dominance of the big states if the president was elected by direct popular vote, and on the other hand, the control of political elites if the choice was made only within the parliament.

But this formula was not uniform even within the same state. Some states allowed a popular vote to choose the electors, while others left the decision to their legislatures. In New York, for example, the local parliament failed to agree, and the state did not even participate in the first election. Despite all this, the process moved forward, because the main goal was not perfection, but to establish the principle of transferring power according to written rules.

When a country chooses "how to choose," it is designing not just one election, but its future crises. Because the decision passes through an intermediate layer, the political struggle over time shifts from "Who do the people want?" to questions such as: How are the votes distributed? Which states become decisive? What happens if a candidate wins the popular vote and loses in the electoral college? These contradictions were not obvious in 1789, but they were inherent in the design itself.

With the rise of the United States as a world power, this model is no longer a domestic affair. It has become a subject of global debate: countries see it as a guarantee of geographical balance, and others see it as evidence that democracy can turn into a conflict of rules and procedures. In every major American electoral crisis, the story of 1789 resurfaces, not as a historical event, but as a starting point for an unresolved debate.

The conclusion that January 7, 1789 leaves us with is both simple and profound: politics is not just about choosing people, but about choosing the rules that govern that choice. When the rules are complex, they may succeed in preventing chaos, but they may create a permanent tension... that is transmitted from country to country, from century to century.

Comments