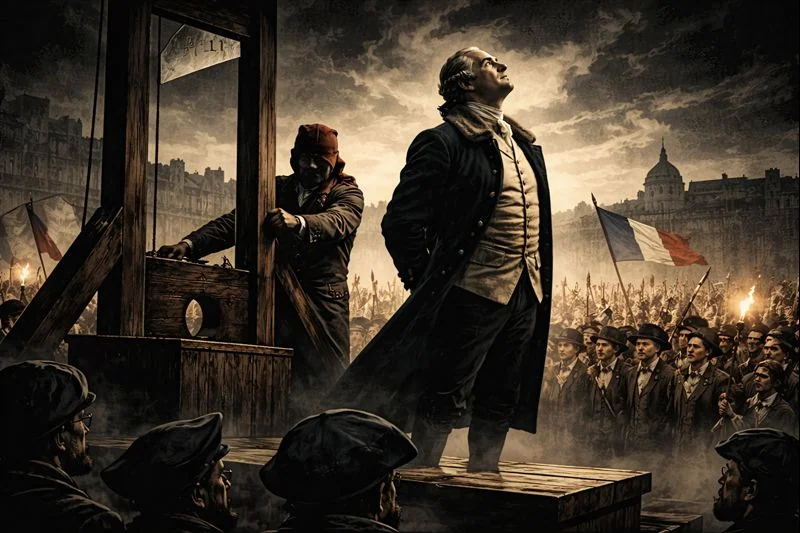

On this day in 1793, Paris witnessed a shocking moment that modern Europe had never known before: the execution of King Louis XVI by guillotine in Revolution Square. The scene was not just the end of an individual's rule, but a definitive declaration of the collapse of the idea of the sanctity of the throne that had formed the backbone of political legitimacy on the continent for centuries. From that moment on, power was no longer understood as a privilege born with blood or a divine mandate, but as the product of human will, accountable and even openly punishable.

To understand why this moment was so symbolically cruel, it must be recalled that the French Revolution began not as a campaign of beheadings, but as a stifling financial and social crisis. The state was nearly bankrupt, the tax system was unfair, the popular and middle classes felt suffocated, and the aristocracy and clergy enjoyed privileges. In its beginnings, the revolution carried reformist demands: a constitution, political representation, limiting the power of the king. But as the few years passed between 1789 and 1793, the struggle shifted from reforming the system to a struggle over the meaning of legitimacy itself.

During this phase, the image of the king changed radically. From the "father king" protecting the subjects, he became, in the revolutionary imagination, the "accused king." Doubts about his loyalty to the revolution increased, especially with the escape attempts and the escalation of the war against the European monarchical powers that saw the revolution as a direct threat.In this context, the trial of Louis XVI was no longer a judicial matter, but a political declaration: the state was no longer the property of a family, and power was no longer a hereditary right. Therefore, the execution was not only a criminal punishment, but a public ritual that announced to the people the transfer of the source of government from heaven and heredity to earth and people.

The modern state was born here, but it was born through a violent act. The guillotine was not only a killing tool, but a political language that said that the old order could not be silently buried, but must be overthrown in front of the public. However, this break created a dangerous paradox: the revolution that overthrew the holiness of the throne produced a new form of holiness, the holiness of the general will, which would later justify revolutionary terrorism in the name of protecting the experiment.

The shock was not only French, but European par excellence. The public execution of a king was a terrifying message to the monarchs of the continent: if the throne falls in Paris, the fear of the throne may fall anywhere. Therefore, royal alliances accelerated, wars broke out, and an existential struggle began between two models of the state: an old model based on hereditary legitimacy and aristocratic alliances, and a new model that talks about citizens, rights and representation. Since January 21, 1793, the French Revolution is no longer an internal event, but a "political infection" that Europe fears.

As a flashback, this moment reveals how the modern state was born out of a bloody break with the past. The execution of Louis XVI was not only the end of a king, but the point of no return: after the head fell, there could be no return to gray compromises. Either the revolution would win or be crushed, either a new legitimacy would be built or everything would collapse. This is why this day remains etched in political memory, not only as a bloody scene, but as a moment that redefined the meaning of governance in Europe and the world.

Comments